If you’ve been keeping up with recent posts this isn’t going to shock you:

I am against dieting. At least in the typical way we approach it.

The Most Effective Weight Loss Plan

If you were told that you had an illness and the treatment option was 2-20% effective, would you do it? What if you were told that a side effect was that it might make the treatment less effective in the future?

You might try it once, but if you were told the actual numbers about the odds of keeping weight off long-term (over 5 years), you would probably think twice before trying another diet. As mentioned above, these odds depend on who was studied and what they did, but the vast majority of people who go on a diet actually gain weight over time (Lowe, Doshi, Katterman, & Feig, 2013).

The Research on Dieting and How It Impacts Us

As I’ve reviewed in several recent posts, dieting is not just ineffective. It has the potential to:

- Make your hormones respond as if you ate much less than you really did (Crum et al., 2011)

- Slow your metabolism significantly, much more than you would expect given your body size (even if you regain weight (Knuth et al., 2014; Fothergill et al., 2016); for a review of the ways dieting impacts our biology, check out my post here.

- Deplete your self-control, so that you have less willpower to control your food intake or exercise, and also less self-control for other important things, like have patience with your family, or tackling a challenging work problem (Hagger et al., 2013; Muraven, Tice, and Baumeister, 1998); Check out the post on this topic about how no one has enough willpower for dieting.

- Erode the basic psychological needs that lay the foundation for thriving in our lives, making habit changes that stick less likely ((Ryan, Patrick, Deci, & Williams, 2008). This was reviewed in more detail in my post here.

The Worst Thing about Dieting

But do you want to know what dieting does that is the most damaging?

It leads smart, capable, and driven people to completely lose faith in themselves.

I cannot tell you how many people I’ve talked to that say:

- I just don’t have the will

- I have no self-control

- I am so addicted to sugar and cannot control myself

- I’m lazy

- I am able to figure out other challenges in my life, except this one

Internalizing Weight Bias

Weight bias is when someone is judged solely by their weight or body size. This has been documented to be prevalent in many settings (healthcare, employment, social settings), and is associated with worse health outcomes.

Another major problem is when people who struggle with extra weight actually internalize this bias. That is, someone who is heavier might buy into the belief that because of this there must be something wrong with them.

I am all for looking inward and working to improve, but we need to also look at and acknowledge our system. The reality is, the approaches we use to help people lose weight and keep it off are not very effective.

The question is, at what point can we stop placing all the blame on the person and start to take a closer look at our system?

But Dieting Sometimes Does Work, Shawn

I hear this a lot. You might know someone who lost 20-40 lbs and kept it off for years. More rarely, you might know someone who lost a larger amount of weight, like 100 lbs, and kept it off for many years without weight loss surgery.

If you are that person, that’s amazing.

If you lose a relatively smaller amount of weight, like 20-40 lbs, that’s also awesome. You probably made significant lifestyle changes and have kept them up. I bet you have found a way to make these changes feel sustainable and do-able and fit into your life.

But it’s important not to say “well I lost 20 lbs and kept it off, so {enter person trying to lose weight that you know} should be able to lose their weight naturally (typically meaning, without weight loss surgery) too”.

We Have to Consider the Biology

For most, losing 20 lbs and losing 100 lbs is most likely totally different from a biological standpoint. The second person is likely fighting up a significantly steeper hill due to all the biological factors associated with weight loss we have discussed.

It’s important to note that there are people who lose a more substantial amount of weight and keep it off. They have been studied in the National Weight Control Registry and on average have lost 70 lbs (32 kg) and kept it off for 6 years (Wyatt et al., 2002).

There are people that do this, but they aren’t the norm. We are still learning from these folks and should continue to do so, but the fact remains that the vast majority of people who attempt a weight loss diet do not fit into this category and therefore we need to look at our systems.

The Message

If you have tried to lose weight multiple times and have regained it

I need you to hear this:

It isn’t you, it’s the system.

There is absolutely hope of you being able to discover ways to make and keep up lifestyle changes, and this may even lead to weight loss, but we need to change the approach. The first step is knowing that the system failed you, not the other way around.

If you have a loved one who is trying to lose weight, or even an acquaintance struggling

I need you to hear this:

It isn’t them, it’s the system.

Please have compassion for them, because your judgment isn’t helping them. In fact, it’s most likely harming them. Weight bias is associated with poorer health behaviors (O’Brien et al., 2016).

This does not mean not taking responsibility to find a solution

If you think I’m saying the above means you or your loved one should give up, I absolutely am not. Just because we have a lot to learn in terms of how we help people lose weight, we actually know a lot about making lifestyle and habit changes that stick and the mindset that truly works for this. So we can use that information to truly make changes that will last, instead of ineffective dieting.

What if They (or I) Stopped Trying and Have Gained Weight?

How many diets do you think that the average person has done?

One study on patients pursuing weight loss surgery found that the average patient had an average of 5 “successful” dieting attempts (meaning they lost 10 lbs or more), and an average lifetime weight loss of 134 lbs (Gibbons et al, 2006).

This is the average. I know from doing thousand of these evaluations that many people have done many, many more weight loss attempts than that.

Given the each effort gets harder from a biological standpoint (and a psychological standpoint), do you really blame them for taking a break from dieting here and there?

We give people the message that weight is all that matters

Over and over, we give people the message that their weight is the most important number when it comes to their health.

We do this by:

- Labeling people based on their body mass index (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) as “morbidly obese” or even “super morbidly obese” (these terms are outdated, yet we keep using them, don’t even get me started on this)

- Telling people (sometimes without even knowing their lifestyle habits) that they need to lose weight to fix XX health problem (some of which are completely unrelated)

- Talking about a “healthy weight” as if a BMI of 18-25 means you are the epitome of health (it absolutely doesn’t)

If someone is unable to keep their weight in a “healthy range” by medical standards, what is their motivation to keep up healthy habits? The system has told them that they are unhealthy no matter what, unless they can get their weight down.

Weight and Health Habits

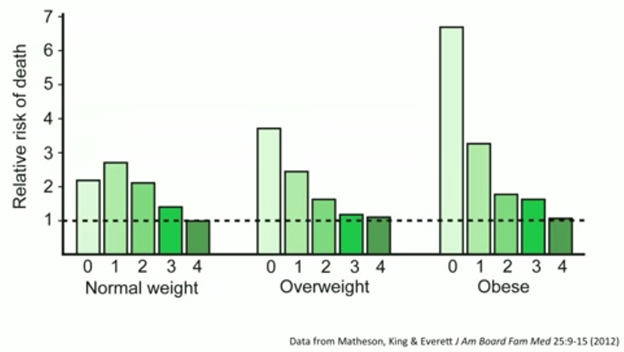

If you saw a person with a weight in the “normal weight” range (BMI of 18-25 kg/m2) and a person with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 taking a jog in your neighborhood, who would you think is at a higher risk of death?

The graph below shows participants in the normal weight (BMI 18-25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25-30 kg/m2) and obese ranges (BMI 30+).

The numbers represent how many healthy habits participants adopted of the following habits:

- Not drinking excessive alcohol

- Not smoking

- Eating a balanced diet

- Regular exercise

The bar labeled 4 means that that group of people is doing all 4 of the habits. Look at the relative risk of death for the normal weight, overweight, and obese groups. What do you notice?

The Habits Make the Difference

You can see that a person with a weight in the obese range, who is regularly engaging in regular exercise, healthy eating, not smoking, and not drinking to excess shows the same risk of death as anyone else doing those behaviors. And their risk of death is lower than a person in the normal weight range who is doing 3 of less of the healthy habits (even if this “normal weight” person is eating well, but not exercising, or vice versa, their risk is still higher) (Matheson, King, & Everett, 2012).

Yet, this isn’t the message we are given and we continue to tell the person with a lower BMI they are healthy regardless of their habits, and the person with a BMI in the overweight or obese range that they are not.

It simply it not accurate, and clearly is not helpful.

Our messaging about weight is making us less and less healthy

Recent data show that our country has gotten even heavier. The percentage of US adults with a BMI > 30 is now up to 42.4% (Hales et al., 2020), up from 35% in 2009-2010 (Flegal et al., 2012), and doubled from 1980.

What we are doing is not working.

5 Ways to Use This Information to Feel Empowered and Hopeful

Ok, enough ranting and soap-boxing from me. Our approach to weight loss is not good and we need to completely re-think it for better health outcomes. The good news is, I do have suggestions for how we can use this information in a helpful and hopeful way.

The tips below will help you challenge our misconceptions about weight loss and feel empowered to take control of our health:

- Focus on habits and feel great about it. Although we cannot always control the number on the scale, we can control our habits. There is great data that eating less processed foods, eating more whole fresh fruits and vegetables, and reducing refined sugar intake is hugely beneficial for our health. We do have control, but focusing on weight loss and that pesky scale is distracting us from what works, and leading us to lose faith in our abilities in the process. It’s time for a new approach to our health.

- Make changes from a place of self-respect. We know a lot about the science of motivation, and the fact is, making changes from a place of freedom and choice, not external pressure means we are more likely to keep up the changes. Dieting rarely promotes change from this mindset, so this is a lot of hope if we can learn to shift our underlying motivation for making changes from “have to” to “want to.”

- Spread this information and work together. Share this post with family and friends. Talk about how what we are doing isn’t working and commit to spending less money on diet and weight loss products and more money and time working together to add more vegetables into your meal preparation plan.

- Challenge the notion that you just “need more willpower.” Despite having this data for many years, few people truly understand how dieting harms them and their loved ones. By educating yourself, you can challenge negative thoughts about yourself being “lazy” or “undisciplined” and realize that this is not true and this messaging is counterproductive. Check out my free guide for 5 ways to use less willpower (aka, set yourself up for success and make healthy habits easier).

- Start or join a health-focused accountability group. Create a group with like-minded people that get the importance of habit changes without a dieting, all-or-nothing approach. Focus on setting realistic goals and celebrating each and every small habit change, instead of solely focusing on the number on the scale.

References

Crum, A. J., Corbin, W. R., Brownell, K. D., & Salovey, P. (2011). Mind over milkshakes: mindsets, not just nutrients, determine ghrelin response. Health Psychology, 30, 424-429.

Fothergill, E. Guo, J., Howard, L., Kerns, J. Knuth, N. et al. (2016). Persistent Metabolic Adaptation 6 Years After “The Biggest Loser” Competition. Obesity, 24, 1612-1619.

Gibbons, L. M., Sarwer, D. B., Crerard, C. E., Fabricatore, A. N., Keuhnel, R. H. et al., (2006). Previous weight loss experiences of bariatric surgery candidates: how much have patients dieted prior to surgery? Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 2, 159-164.

Hagger, M. A., Panette, G., Leung, C., Wong, G., Chan, D. K., et al. (2013). Chronic inhibition, self-control and eating behavior: Test of a ‘Resource Depletion’ Model. PLoS ONE, 8, e76888. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076888

Knuth, N. D., Johannsen, D. L., Tamboli, R. A., Marks-Shulman, P. A., Huizenga, R. et al. (2014). Metabolic adaptation following massive weight loss is related to the degree of energy imbalance and changes in circulating leptin. Obesity, 22, 2563–2569.

Matheson, E. M., King, D. E. & Everett, C. J. (2012). Healthy lifestyle habits and mortality in overweight and obese individuals. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 25, 9-15.

Muraven, M., Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 774–789.

O’Brien, K. S., Latner, J. D., Puhl, R., Vartanian, L., Giles, Cl., Griva, K., & Carter, A. (2016). The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite, 102, 70-76.